Aegyptum imperio populi [Ro]mani adieci (Res gesate divi Augusti, I. 27): “I added Egypt to the empire of the Roman people”

Suetonius relates that upon Augustus’ death the Vestals delivered to the Senate his will and three sealed volumes that were opened and solemnly read. One of the documents was the Index rerum a se gestarum, also known as the Res gestae divi Augusti, written personally by Augustus. The original text was lost during the Middle Ages, and it was not until 1555, when, during Austria’s wars with the Turks, ambassadors sent by Emperor Ferdinand I of Habsburg to Sultan Suleiman the Great discovered a mutilated reproduction of the Roman inscription in Ancyra (now Ankara), formerly the capital of Roman Galatia. It was located in the ruins of the temple dedicated to the god Augustus and to the goddess Rome, engraved in Latin on the two walls of the temple’s pronaos; the Greek version was engraved on the right wall of the cella. This first important discovery was followed by the discovery of other fragments of the text from the monumentum Apolloniense, i.e., a marble base erected at Apollonia of Bithynia (now Abuliond in Turkey) between 14 and 19 AD with the Greek text engraved on it. Finally, two successful archaeological campaigns (1914 and 1924) in the city of Antioch of Pisidia (now Isparta province, Turkey) brought to light -in the area of the ruins of Augustus’ temple- forty-nine fragments of an inscription reproducing the Latin text of the Res gestae.

What does Augustus record in his will about the Battle of Actium and the annexation of Egypt? Very little really: a brief and concise sentence. But what did the annexation of Egypt to the Res Public, that is, to the nascent Roman Empire, really mean?

The Battle of Actium on Sept. 2, 31 BC marked a pivotal moment in ancient history: the end of the last of the Hellenistic kingdoms, the Ptolemaic one, the illustrious heir to the millennia-old and stratified ancient Egyptian culture. But the end of Cleopatra’s reign by no means meant the erasure of a thousand-year-old, stratified culture. On the contrary, from that moment on, Egypt definitely opened the doors of its temples and palaces to Rome, impressing it with its artistic and cultural richness.

The thematic itinerary Discovering Egypt in the Parco archeologico del Colosseo explores precisely the Roman reception of the culture of ancient Egypt, focusing on the heritage of the PArCo. Rome did not, in fact, simply import and emulate, but developed a unique and authentic language of references and cross-references; an artistic language that spoke to the Roman citizens of the Urbs and of the entire Res Publica, now extended far beyond the Mare Nostrum. After more than 2,000 years, some of this language may be difficult to understand, a kind of distant echo of an artistic-cultural fashion, but it was instead very clear to those who lived in the Roman Empire, from the time of Augustus to that of Maxentius. In the Female Herms of the Temple of Apollo in Rome, commissioned by Augustus in 28 BC, we catch the suggestion of ancient Egypt in the proud and almost sacred pose of the four Danaids; the Nilotic scenes of the House of Livia on the Palatine bring us back to the shores of the sacred river; the Aula Isiaca on the Palatine shows us a Ptolemaic-Egyptian deity with a Roman appearance, finely surrounded by symbolic references to ancient Egypt; the use of red porphyry in the time of Maxentius, in the Temple of Divus Romulus, brings us back to quarries on the Red Sea, already exploited by the Ptolemies and enhanced by the Romans. These are some of the suggestions that the itinerary will touch on, showing how and where in the Parco archeologico del Colosseo the ancient fascination of the Pyramids and of Alexandria remains.

The House of Augustus on the Palatine

Around the middle of the fifth decade of the 1st century B.C. a wide range of Egyptianized motifs such as lotus flowers, uraeus, obelisks and sphinxes, which can be traced back to the Alexandrian taste, were used to decorate some rooms of Augustus’ residence on the Palatine. The particularity of this Egyptianized taste lies in the fact that it dates back to an historical period when relations between Rome and Egypt were ambivalent. Ever since Caesar’s death in 44 BC, in fact, Octavian – the future Augustus – had openly and officially lashed out against the Egyptian religion and cults practised in Rome, manifesting an apparent aversion to the Nilotic culture. Actually, his reserve was more related to his rivalry towards Cleopatra and Mark Antony than to an actual rejection of Egyptian culture. The latter, in fact, clearly entered the Palatine residence of the first emperor: in the upper cubicle of the House, and also in the Aula Isiaca -a rich room discovered under the Basilica of the Domus Flavia in 1912, perhaps also part of the Augustan property- many details reflect an ‘exotic’ taste: a sort of ‘fashion’ reinforced by the stay of Cleopatra and her court in Caesar’s gardens in Trastevere between 46 and 44 BC. It is remarkable that this fashion reached a peak precisely in this historical period: probably the refined artistic environment of Alexandria in Egypt offered in those last decades of the 1st century BC cues for a decorative manner that also inspired the painters of the Domus of Augustus. Although now deprived of their original meaning and reduced to almost exclusively decorative motifs, numerous elements and symbols from Ancient Egypt are depicted in the frescoes, particularly in the Isiac Hall and the Upper Cubicle of the House of Augustus.

Fig 1. The so-called “Small study” in the House of Augustus on the Palatine Hill

Fig 1. The so-called “Small study” in the House of Augustus on the Palatine Hill

The Aula Isiaca

On the walls of this mysterious apsidal hall, candelabra and plant scrolls stand out, from which ‘ribbons’ spread out in a sinuous and symmetrical movement, creating exotic and variegated lotus blossoms; looking more closely at these decorations, one can also identify pharaonic attributes, in particular urai and crowns transformed into decorative elements.

Let us see what meaning these elements had in Ancient Egypt by looking at them in the words of the Egyptians themselves.

– Lotus flower. Seshen is the name the Egyptians gave to this flower. The lotus is the flower of Nymphaea and in Egypt it grew in the marshy areas of the Nile in two varieties: the white lotus and the blue lotus. The blue lotus was particularly sacred to the Egyptians: it opened every morning, with its intense golden centre surrounded by blue petals, interpreted by the ancient Egyptians as an imitation of the sky’s greeting to the sun, releasing a sweet perfume. Every afternoon the petals would close again and reopen the next day. The flower was thus closely linked to the rising and setting of the sun, and to the sun god himself: the myth tells how a lotus, which emerged from the primordial waters, became the cradle in which the sun was born each morning. “I am he who rises and illuminates wall after wall, everything in succession. There will not be a day that lacks its due illumination. Pass, O creature, pass, O world! Listen! I have commanded you to do so! I am the cosmic water-lily rising from the black primeval waters of Nun, and my mother is Nut, the night sky. O thou who hast made me, I have arrived, I am the great ruler of Yesterday, the power of command is in my hands’. – Spell 42, The Book of the Dead

– Uraeus. It was the representation of the cobra snake, sacred to the goddess Uadjet. The goddess was worshipped particularly in Lower Egypt and with the union of the two kingdoms became one of the two patron deities of the pharaoh. A snake-shaped decoration originally placed on either side of the solar disc, the uraeus later recurred on the headgear of Egyptian kings and queens as a symbol of strength and power. The uraeus is also mentioned in theogonic tales as an “incinerating cobra”, i.e. a deadly weapon. Sacred legends tell, in fact, that this snake was on Horus’ forehead when the god went to the battlefield accompanied by his companions. With its fiery breath, the uraeus incinerated the enemy. “I am the serpent Sata torn by the years. I die and am reborn every day. I am the Sata serpent dwelling in the deepest recesses of the earth. I die and am reborn and renew myself by rejuvenating myself daily’. – Spell 87, Book of the Dead

– Pshent (double crown). The pshent or double crown is the outcome of the union of the red crown and the white crown (deshret and hedjet), to which uraeus and vulture are often added. The pshent crown designates the pharaoh as the ruler of the whole Egypt and was also worn by certain divine beings considered mythical rulers of Egypt, such as Atum and Horas. The red deshret of Lower Egypt was the outer part of the crown; it had a curled protrusion at the front representing the proboscis of a bee and in fact the term deshret also indicated the bee. The red colour represents the fertile land of the Nile delta. The white crown, hedjet, was the inner crown, more conical and with cutouts for the ears. It was worn by the pharaohs from the First Dynasty around 3000 BC. The double crown was a fusion of the white crown of Upper Egypt and the red crown of Lower Egypt. Another name for it is shmty, meaning ‘the two mighty ones’ or sekhemti. During the Ptolemaic dynasty, rulers wore the double crown when in Egypt; when they left the country they wore a diadem.

– Atef crown. This is an elaboration of the white hedjet crown adorned with ostrich feathers. This crown consisted of a tall tiara, placed on top of a pair of horns, at the sides of which two large feathers were attached; it is found in representations of the pharaoh as well as in those of other deities such as Osiris and Khnum. During the New Kingdom, this type of crown underwent an evolution through the addition of further symbols, such as the uraeus and the solar disc. It was considered a symbol of royalty and at the same time a representation of the diurnal star. It was the crown of the gods, worn by Osiris, Horus, Ra, Amun, Ptah, Min, Hathor, Isis and also Sobek. It only appears on the heads of pharaohs from the 18th dynasty onwards. Queen Hatshepsut was the first to wear the atef crown. After her: Amenophis III, Ramesses II, Ramesses III and some rulers of the Ptolemy dynasty.

Fig. 2. Aula Isiaca, detail of the vault decoration.

The Danaids in Apollo’s Temple

The female herms from the Temple of Apollo introduce us to a fascinating theme. Today we identify them with the Danaids, the 50 daughters of King Danaos, who were forced to marry the sons of Egypt: instigated by their father, they killed the newlyweds on their wedding night. Only one of them, Hypermestra, saved her husband Lyceus’ life and helped him escape. As a punishment, the Danaids were condemned to fill a bottomless barrel with water for eternity. The interpretation of the Herms as Danaids opens up interesting horizons on the possibility that the first emperor of Rome wanted to allude to the victory of Actium not only as the end of a civil war, but also as the painful re-establishment of a much-desired peace. Their position within the Numidian marble colonnade connected to the temple of Apollo Actium, in fact, could allude precisely to the victory over Cleopatra and to the annexation of Egypt. The allusion is even more obvious if one considers that the same marble used for the herms, ancient red and ancient black, probably came from Egypt. Recent reconstruction proposals emphasise that the female herms were only some of the actors in the story told in the portico of the temple of Apollo. In fact, Latin sources also mention the presence of their father, Danaos, and their cousins and betrothed, the sons of Egypt. The portico must, therefore, have appeared as a theatre in which the elegant female herms – the Danaids – and the dynamic warriors on horseback – the sons of Egypt – staged a tragic and dastardly myth.

Fig. 3. The Danaid herms in black and ancient red marble now on display at the Palatine Museum.

Why did Augustus choose this very myth for the temple dedicated to Apollo? The answer is not unequivocal, because the language of Augustan art is deliberately ambivalent. The myth of the Danaids is a myth of revenge and suffering, all the more serious because it occurred within the same family. Direct, therefore, is the link with the pain and ferocity of the recent civil war. At the same time, the Danaids represent opposing aspects: they are murderers and avengers, victims and executioners, to such an extent that, if we wanted to interpret their dastardly deed as a metaphor for the battle of Actium, we could not say whether they represent the barbarian East and Cleopatra herself, or the Roman West. Probably there is no certain part for the actors involved, because if it is true that Mark Antony was defeated and Egypt annexed, it is also true that he did not fight against barbarians or foreigners, but against his Roman brothers themselves and in a land, Egypt, that at least since the 2nd century BC had entered Rome with its gods and art. In the portico of the Danaids, therefore, where a tragic story led to the temple of Apollo, there were neither winners nor losers: the Egyptians attacked, and were killed; the Danaids, victims of an abuse of power, became cruel, performed a wicked act without pity and had to atone. A myth, in short, from which to draw an open and deliberately ambiguous lesson.

Fig. A Reconstruction of Apollo’s Temple (from A. Carandini, P. Carafa, Atlante di Roma Antica, 2012)

Fig. A Reconstruction of Apollo’s Temple (from A. Carandini, P. Carafa, Atlante di Roma Antica, 2012)

Egyptian wheat in the PArCo: the Horrea Agrippiana

Egypt was of crucial importance in imperial Rome not only for the precious materials and millenary culture that reached the Urbe from the Nile, but also for wheat, a fundamental resource in antiquity. From the conquest of Alexandria on 1 August 30 BC, Egypt, together with North Africa, became one of the main suppliers of this foodstuff for Rome. Once the grain arrived in Rome, it was stored in special facilities: the horrea (warehouses). In the Parco archeologico del Colosseo are some of the most important warehouses for Egyptian grain: the Horrea Agrippiana, ‘Agrippa’s warehouses’. Their construction was commissioned in the last years of the 1st century BC by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, the general of Augustus, who wanted to name the horrea after his daughter Vipsania Agrippina, future wife of the emperor Tiberius. We can admire the remains of this imposing building, adjoining Santa Maria Antiqua and the group of Domitian buildings, in the Roman Forum, where the Vicus Tuscus leads from the slopes of the Palatine towards the Velabrum. The building had two floors with rooms opening onto a large inner courtyard that was partly porticoed; along the street the horrea were surrounded by tabernae (shops). In the centre of the courtyard is a small room, which still has its black and white mosaic floor. Here was found an inscription dedicated by three merchants to the Genius horreorum and the Genius of Agrippa (hence the identification of the structure with the Horrea Agrippiana). The importance of the Horrea Agrippiana is linked not only to Agrippa’s public figure, but also to their specific function of Egyptian wheat storage. In fact, the horrea are tangible evidence of a series of reforms by Augustus with Egypt at their centre. After his conquest, in fact, the princeps turned Egypt into a territory under his strict control, to which senators travelled only with his authorisation. He also established two public offices centred on Egypt: the prefecture of Egypt and the prefecture of the annona. The prefect of Egypt, established in 29 BC, had the task of governing the province under a direct mandate from the emperor. The prefect of the annona, established probably between 8 and 14 AD, on the other hand, was responsible for the transport and storage of foodstuffs destined to Rome, a large percentage of which was wheat produced in Egypt and North Africa.

The grain was stored in local horrea and then transported by sea to the main ports in Italy. However, during the winter months, from October to March, the Mediterranean Sea was considered mare clausum: ships tended not to sail during those months, except at their own risk. The tons of grain and cereals needed for Rome’s annual consumption (about 25,000, a substantial percentage of which came from Egypt) had, therefore, to be transported by an impressive number of ships and in only six months of the year. Arriving on the Italian coast, the ships unloaded the foodstuffs at two main ports: Puteoli (Pozzuoli), where the harbour could accommodate the very deep-hulled cargo ships, and at Ostia, where the ships anchored far from the coast and the foodstuffs were unloaded by means of flat-hulled vessels. The Horrea Agrippiana were, therefore, one of the final destinations of the most important resource of antiquity, grain, which, from the banks of the Nile and by means of large honorary ships, crossed the sea to arrive along the river Tiber in Rome, in the area of today’s Parco archeologico del Colosseo.

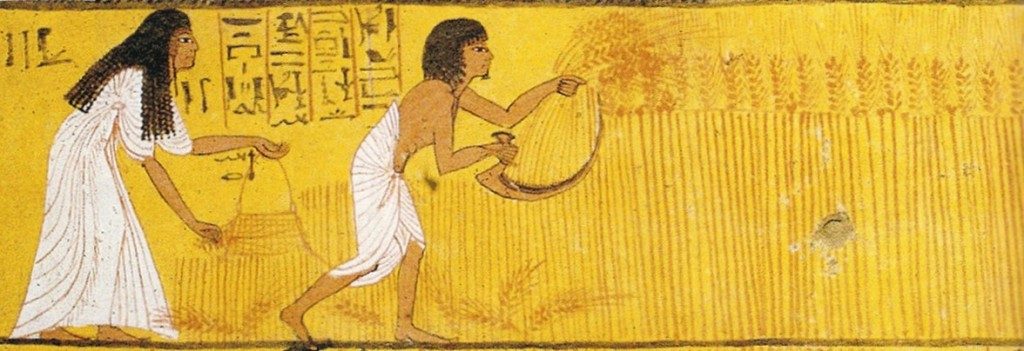

Fig. 5. Deir el-Medina, Tomb of Sennedjem: the deceased and his wife ploughing a wheat field (image from Wikimedia)

Juturna and the Nile: when the river touches the springs

Egypt once again returns to the Roman Forum, near the Horrea, in an area so sacred to Rome that its presence could even be considered be ‘too exotic’: the area of the sacred spring of Juturna. On the north-western slopes of the Palatine, between the temple of the Càstori and the house of the Vestal Virgins, the goddess Juturna was already worshipped in archaic times. She was the goddess of the springs that flowed from here and the patron deity of all those who worked with water, such as the potters. It is precisely water that is the link here between the two worlds, the Nilotic-Egyptian and the Roman-Italic. In the area of the Lacus Iuturnae, along the corridor in front of the tabernae, in fact, two fragments of the only figured mosaic floor found in the Roman Forum are preserved: in their weave of black and white tesserae is represented the Nile, Egypt’s most sacred water source. The Fountain of Juturna had already been given a monumental appearance in the Republican age, but it was not until the late imperial renovations that the goddess was associated with the image of one of history’s most famous rivers. The choice to represent the river of Egypt, therefore, is not accidental: what better reference to honour the water of such a sacred and ancient source of Rome than the river that made life flourishing in Egypt? This is clear from the fishing scene depicted in the two mosaic fragments: men in boats are intent on juggling the waves, surrounded by fish and an almost bored ibis. This is a genre scene with subjects related to the aquatic world, which, in terms of technique and style, is fully within the Roman figurative repertoire of the late 3rd century AD. Indeed, the transfer between the 3rd and 4th century AD of the statio aquarum from the Campus Martius to the Roman Forum, seems to have destined the area of the Lacus Iuturnae to the function of ‘water office’.

Fig. 6. The Fountain of Juturna after the recent restoration works

It is remarkable that, if during the first years of the Roman Empire, at least until the time of Caligula, Egyptian cults were publicly forbidden, during the late Empire, at the dawn of the rise of Christianity, Egypt and its sites were by then so integrated into Roman imagination that they were depicted in a floor in asacred area such as that of the Fountain of Juturna. The ParCo accompanies us elsewhere in this historical, almost epochal transition: from the private and mysterious Aula Isiaca of the Domus Augustana at the centre of the Palatine Hill, to the Nilotic scenes of the public and sacred Lacus Iuturnae.

Fig. 7. Fragment of the Nilotic mosaic preserved by Juturna’s spring.

| THE NILE IN MYTHOLOGY AND ART |

| The ancient people of the Nile valley believed that the waters were under the domain of Sobek, a deity represented in the form of a crocodile. Life in Egypt was strictly linked to the river’s floods, so this phenomenon was deified as far back as the Old Kingdom. The ancient Egyptians, in fact, worshipped Hapy, the incarnation of the fertility of the flooding of the Nile River. As the Berlin Papyrus states: ‘The image of Hapy who is half man and half woman’, Hapy was depicted as an obese man with an opulent belly, long beard and pendulous breasts. The icon of Hapy in sacred processions alternated with female figures, thus representing the union between the overflowing water that is man and the fertile earth that is woman.

The ancient Egyptians also believed in the existence of an underground river, a Nilo-Nun, flowing in the Amduat, i.e. in the Underworld. Every year the Nilo-Nun emerged from an underground cavern, Tephet, and, becoming the Nile proper, flooded the earth. In this cavern, from the 18th dynasty (New Kingdom) was believed that the god Hapy also resided. The Tephet cavern thus represented both the primordial water from which everything was created and the annual renewal of that creation. In ancient texts, the Nile, once out of Tephet, could flow from two different caverns, called Qerti. These were the mythical expression of the character of the river’s flood, fertile and terrible at the same time. In Greek mythology, on the other hand, the river Nile is represented as a deity in its own right, but of lower rank than the other gods of the pantheon. Already Hesiod in his Theogony (vv. 337 ff.) reports its genealogy: ‘Thetis begat to Ocean the swirling rivers, / the Nile, the Alphaeus, the Eridanus with deep whirlpools (…)’. Nile, therefore, was considered a very ancient deity by the Greeks, almost on a par with the titans. Being the personification of the river of the same name, the god was attributed both an anthropomorphic and a teriamorphic appearance. Nilus fathered numerous sons, including Menfi, Ankhinoe, Anippe Khione, Kaliadne, Polixo and Telefassa. The most important among them was Memphis, who begat Libya along with Epaphas, the king of Egypt; Memphis was also the mother of the twins Belos and Agenor, who married Ankhinoe and Telefassa, two of Nile’s own daughters. The spread of the cult of the Nile in the Roman sphere is to be connected with the Greek pantheistic theories, which elected personifications of rivers and mountains as deities; this tendency is also characteristic of Roman religion (as for the similar cult of the Tiber). From the second half of the 1st century A.D., in fact, both material culture, such as imperial coins bearing the legend deo sancto Nilo, and the institution of special festivals, such as the Νειλαῖα (Neilaia), testify to the growing cult of the Nile. During these festivals, propitiatory for floods, allusion was made to the sacred union of Osiris with Isis, the Nile fertiliser of the land of Egypt. Although this cult was abolished by Constantine, the propitiatory rites and ceremonies of the sacred union continued for several centuries. The Greco-Roman artistic iconography of the Nile reflects its character as a beneficent deity with fertilising powers: despite their abundance and variety, Greco-Roman works commonly depict the river as a reclining elder endowed with attributes of fertility and prosperity: the cornucopia, the grain, and the 16 cubits of water growth usually represented by putti. |

Lights and shadows on the Palatine: the Isiac oil lamps

The Palatine, site of the imperial palaces, was also a place of worship of Egyptian gods. From 1860-1870, with Rosa’s excavations, until the more recent campaigns of the 1980s, the Domus Tiberiana has yielded a considerable amount of Isiac oil lamps, which are now kept in the PArCo deposits. The oil-lamps come from three rooms in the part of the Domus destined for the servants, the storerooms and the soldiers’ guard posts: located in inner areas of the ground floor, the three rooms were communicating with each other and are located in the area of the Palatium that turns towards the clivus Victoriae. Typological comparisons and excavation data allow us to date the oil lamps in the Severan age (193-235 AD). The typology of the oil lamps, their location and dating are evidence of the existence in the Domus Tiberiana of a centre of Isiac worship. The rooms in which the oil lamps were found must have been the sacellum of the cult: the characteristics of these rooms, interior and hidden, small and without windows, well reflected the requirements of the Isiac rites, in which the deity was worshipped for only two hours a day inside a sort of sancta sanctorum. Priests and worshippers of the Isiac cult practised in the Domus Tiberiana were the employees of the emperor’s family. It is no coincidence that Isiac cults were widespread among slaves, freedmen, merchants, soldiers and foreigners. Furthermore, according to Aurelius Victor, we owe the effective introduction of the ‘sacra Aegypti’ in Rome to Caracalla, bringing the cults into the pomerium and substituting Jupiter with Serapis as protector of the emperor. The sockets of our oil lamps depict Isis and Serapis. in pairs or isolated, recognisable by characteristic elements: Isis has a closed robe with the Isiac knot; her headdress has horns and feathers, sometimes replaced by ears of corn, and is surmounted by the solar disk. Serapis is an adult man with a beard and wavy hair; he wears the characteristic modion on his head, according to the original cult image in Alexandria. Besides them, Harpocrates is also depicted in the oil lamps: a short-haired boy with the index finger of his hand held over his mouth. Some of the oil lamps also depict special moments, such as the kiss between Helios and Serapis. The scene takes us directly to the Serapeum of Alexandria, where there was a mechanism introduced by Caracalla after the disastrous fire of 181: in the sanctuary, as the sunlight -entering through a small window – rested on the lips of the cult statue of Serapis, a metal simulacrum of Helios, attracted by a magnet on the ceiling, rose into the air.

In Egyptian cults, Isiac lanterns had multiple purposes. As the rites were celebrated in hidden places, oil lamps became the protagonists of clever plays of light and shadow. In other cases, oil lamps could be placed as votive offerings, becoming part of the furnishings of the place of worship. Finally, oil-lamps could also be used during rituals that took place in daylight: among the Isiac priests who paraded in the annual processions are also mentioned the lychnophoroi, the lamp-bearers. Complex rituals, therefore, also those dedicated to Egyptian cults on the Palatine: in all cases, Isiac oil lamps played an important role.

Fig. 8. The Domus Tiberiana seen from the Roman Forum

Red porphyry in the Parco archeologico del Colosseo

Among the mirabilia of the Parco archeologico del Colosseo the Temple of Venus and Roma, the Basilica of Maxentius and the Temple of Divus Romulus share a common feature of clear Egyptian origin: the red porphyry.

The entrance to the Basilica of Maxentius from the Via Sacra was, in fact, a wide staircase leading to an atrium with four columns (tetrastyle) of red porphyry. Also made of red porphyry are the columns of the portal of the Temple of Divus Romulus, which opened on the Via Sacra Summa, between the Arch of Titus and the Roman Forum square. Both buildings have great symbolic significance: a monumental basilica and a temple. The use of red porphyry in these monuments where the precious material was most visible, i.e. at the entrances, should therefore not have been accidental.

Figure 9. Porphyry columns in the Temple of Romulus.

In the Temple of Venus and Roma, on the other hand, red porphyry is used for the cellas, the heart of the temple: red porphyry is used for the columns leaning against the main walls; in porphyry are also the two columns preceding the apse reserved for the statue of Roma; as is the marble opus sectile of the floor.

Fig. 10. The Temple of Venus and Roma. Porphyry is used for columns and paving.

Highly valued in antiquity for its purple colour, red porphyry was understood as a symbol of divine and royal power. Very difficult to work, red porphyry became a symbolic material, a symbol of nobility, prestige and wealth. However, perhaps because of its hardness, it was little used in the time of the pharaohs. It was not widely used in Egypt until the Ptolemaic era, becoming one of the most prized and expensive building stones over the centuries. Red porphyry was introduced to Rome in the Julio-Claudian era: with the discovery of quarries in 18 AD by Gaius Cominius Leugas. Its use reached its peak from the beginning of the 2nd century AD to the middle of the 5th century AD, when quarrying ceased. The quarries were imperial property, which ensured the availability of material for major public building programmes; what was left over was resold at a high price for private use: 250 denarii per cubic foot, according to Diocletian’s edict of 301 AD. Red porphyry did not exhaust its symbolic charge even when quarrying ceased; on the contrary, it was increasingly associated with the divine and imperial spheres. Even Charlemagne was crowned in the 9th century by Pope Leo III on the ‘Rota Porphyretica’ of St. Peter’s, the large 2.6 m red porphyry disc currently standing just beyond the nave entrance. The disc, already present in the 9th-century basilica and probably of pre-Constantinian origin, was of such great importance that it could not be trodden on for any reason by the common people.

The ancient red porphyry quarries were located in the Egyptian Eastern Desert, at the centre of the caravan routes that connected the trading poles of the Nile Valley with the ports of Myos Hormos and Berenice. The quarries were located on the eastern slope of today’s Gebel Dokhan (‘Smoking Mountain’), which the Romans called Mons Porphyrites or Mons Igneous (‘Mountain of Fire’), in the ancient region of Thebaid. The name Mons Porphyrites was due to the red colour of the rock and from it extended to the material quarried, Lapis Porphyrites, known today as ‘Ancient Red Porphyry’. As many as six quarries compatible with the Ancient Red Porphyry type have now been found, all located on the eastern side of the mountain, at different altitudes. In Roman times, the quarries were managed directly by the imperial entourage: such was their importance that, under the Emperor Tiberius, they were equipped with a defensive fort to guarantee their security.

The porphyry was transported by sea by the naves lapidariae, each capable of carrying 100 to 300 tons of marble, considering that porphyry, depending on the height of the column, could reach up to 126 tons per piece. Ships directed to Rome docked at the statio marmorum in Ostia. From here the marbles flowed up the Tiber to storage warehouses, such as the statio marmorata under the Aventine. The valuable material finally arrived to the marble workers’ workshops. We can imagine a similar path for the precious red porphyry columns of the Temple of Venus and Rome and the Temple of Divus Romulus, from the quarries of Mons Porphyrites to the present-day Parco archeologico del Colosseo.

Egyptian reliefs from the Palatine: a mystery from the Domus Flavia

Palatine, 1912: Giacomo Boni archaeologically investigates the Domus Flavia. Excavating in the area of the peristyle in front of the Coenatio Iovis, around the labyrinth fountain, Boni finds three “fragments of a low Egyptian relief carved on a slab of Greek marble”. Two of these match, the other, although similar in workmanship and style, is spurious

Palatine, 1936-37: Alfonso Bartoli finds a fragment of a relief painted with a series of Egyptianized crowns, reused in a building located between the so-called Stadium and Vigna Barberini. According to Bartoli, the fragment also comes from the area of the Domus Flavia.

Let us also take a step back. Palatine, 1867: Rosa discovered in the Domus Flavia a cylindrical base of a statue with an inscription of dedication to Serapis. The patron is a certain Aurelius Mithres, at first slave of the emperor, later a freedman.

Figure 11. Fragments of Egyptian reliefs found on the Palatine by Giacomo Boni (top) and Alfonso Bartoli (bottom)

Three different generations of archaeologists have thus brought to light evidence of Egyptian cults on the Palatine, all centred around the Domus Flavia. The freedman Mithres, in fact, had dedicated a cult statue on the Palatine to Serapis, a deity of the Ptolemaic pantheon of Egyptian derivation. The reliefs found by Boni and Bartoli depict emblems, deities and ritual scenes typical of Ancient Egypt. But when do these finds date back to? The freedman’s surname, probably Aurelius, and the epigraphic style allow us to date the base to the 3rd century AD. The four fragments, on the other hand, judging by the style and the original location in the Domus Flavia, can be dated between the end of the 1st century AD and the beginning of the 2nd century AD. The fragments found by Boni are engraved in low relief and depict deities and hieroglyphics. Whatever their original function in the peristilium, the artist’s skill in emulating the Ptolemaic reliefs of Thebes, Karnak, Edfu and Dendera is remarkable: the models, though, were not the reliefs of Pharaonic classicism, but the Hellenistic-Roman ones that the artists themselves could easily see in person when travelling in Egypt. The fragment found by Bartoli shows the same sacred character, although the artist’s hand is different and probably tries to imitate, though not fully understanding, the models of the classical Pharaonic era.

Considering that the cult of Isis and Serapis on the Palatine developed significantly from the age of Caligula to the Domitian era, it is within this period that the fragments must be dated. It was precisely under Domitian that numerous original monuments from the Pharaonic and Ptolemaic era came to Rome. The emperor’s afflatus Aegypti was such, that, for example, the obelisk that still stands today in Piazza Navona was erected in those years. Even in the case of our reliefs, it is plausible to assume that they were made in Egypt and then brought to Rome. These important fragments, some of the most significant evidence for the existence of Egyptian divinities on the Palatine in the early centuries of the empire, are currently stored in the PArCo warehouses.

Let us take the opportunity to take a closer look at them…

| THE FIRST GROUP OF FRAGMENTS FOUND IN 1912 (fig. 11 top) |

| Two of the fragments found by Boni show as many as four hieroglyphic signs, two of which are correctly written, and a theory of deities, two of which are preserved. The deities are seated in the classical resting attitude that can be seen in the original late Pharaonic and Ptolemaic bas-reliefs. Who these deities are is still a mystery: the divine attributes, such as the bonnet-like headdress on which the uraeus with the solar disc stands, only make it clear that they are male deities. Too worn or poorly understood by the stone carver who sculpted them, no other attributes allow them to be identified. Yet the sacred and religious character of the relief is clear: theories of male and/or female deities, each distinguished by their own emblems and in a seated position, were very frequent in the reliefs of Ptolemaic temples. In those reliefs, the figure of the Pharaoh, standing before the deities, stood out in the composition. The fragments from the Palatine clearly show the fascination for a foreign religion that had by then been accepted up to the highest ranks of the Empire. |

| THE THIRD FRAGMENT FOUND IN 1912 |

| The third fragment found in 1912 testifies to the extent to which the ancient Egyptian heritage had been passed down, in a perpetual evolution, from the hieratic Pharaonic past to the more naturalistic Ptolemaic Hellenism. The artist, again, drew inspiration more from Ptolemaic Egypt than from Pharaonic classicism. All that is preserved of the main deity is a hand clasped around a sceptre in the form of a papyrus column: too little to understand who he was. However, her left-facing posture and the presence of the hieroglyphic egg reveal that she is a goddess, depicted in the usual posture of Egyptian reliefs. Beneath her rests another god, clearly visible, but not of obvious identification. It should, in fact, be the ox Apis, but the gentle lines of the relief and the classic solar disc between the horns, replaced by a mitre of an oriental character, are indications of a contamination that is not accidental. Rather than the Egyptian Apis (FIG. 6), could it be the god Orisis-Apis, i.e. Sarapis? Would it then only be a coincidence that the freedman dedicating the base in the 3rd century was called Mithres Serapis? |

| THE FRAGMENT FOUND IN 1936-37 (fig. 11, bottom) |

| The fourth fragment, found by Bartoli in 1936-37, depicts four deities of which unfortunately only the crown remains. Analysing the type of crown and the associated emblems, we recognise three of the most renowned deities: Osiris, Ptah and Isis with the child Horus. Looking at the fragment from right to left, as one does for Ancient Egyptian funerary reliefs, the first emblem turns out to be a variant of the Upper and Lower Egyptian crown with a central solar disc: it is Osiris in the Hellenistic-Roman version of Osiris-Sokaris or, fascinatingly, Sarapis, a direct emanation of Osiris-Sokaris.

The second emblem reproduces the atef crown with a hieroglyphic legend indicating the deity Ptah; of the third crown only the upper part remains, characteristic of the white Upper Egyptian crown: too little to speculate which deity it belonged to. Finally, the fourth emblem is the atef crown with the solar disc between the cow’s horns: this is Isis in her role as divine mother, seated on the throne of the gods with little Horus on her lap. The artist here drew clear inspiration from the walls of Pharaonic tombs, rather than from funerary stelae, making his own, albeit with some misunderstandings, decorative and iconographic themes widespread throughout the history of Ancient Egypt. |

Hathoric capitals in the Palatine Museum

Who was Hathor? In Egyptian religion, Hathor was the goddess of joy and love, motherhood and beauty. She was extremely popular, and we have many ancient sources speaking of her, attributing her the role of goddess of music and dance as well as fertility. She was commonly depicted as a cow with the sun disc, equipped with an uraeus, on her head, between her horns. The ancient Greeks not surprisingly associated her with Aphrodite.

In the Palatine Museum’s collection Hator can be spotted in two white marble pilaster capitals: one can see her bovine ears that, together with her typical hairstyle – a wig with two long locks ending in outward curls – frame a human face. Two cobras stand erect from the hair, one with the crown of Lower Egypt and the other with that of Upper Egypt. Above the head is a small temple from whose central niche a cobra emerges: and let us remember that the cobra is precisely an Egyptian symbol of Pharaonic kingship, known as the uraeus. Capitals of this type are very rare in Italy and instead very frequent in Egyptian temples dedicated to the goddess in the Pharaonic and Greco-Roman periods. The building of origin of the capitals, found on the Palatine hill, is not known: the comparisons that can be made -e.g. with the slab representing a scene of adoration with priests on either side of a Hathoric capital exhibited in the Archaeological Museum of Velletri- lead us to propose a date in the Augustan age.

By Francesca Boldrighini, Astrid D’Eredità, Federica Rinaldi, Andrea Schiappelli (Ufficio comunicazione del Parco archeologico del Colosseo)

Texts by Costanza Francavilla.