GLADIATORS IN THE ARENA. BETWEEN COLOSSEUM AND LUDUS MAGNUS

Details

- Colosseum and Ludus Magnus: a revived connection

- The Origins of Gladiators

- The Gladiators' Couples

- Room 2 Helmets of Murmillo and Thraex

- Room 3 - Helmets of Murmillones

- Room 4 - Murmillo and Thraex

- Room 5 - Secutor, Retiarius e Provocator

- Room 7 - The Hoplomachus

- Room 8 - Parade Helmets

- The Gladiators' Glossary

- Bibliography

- Colophon

- Download the ebook

Share

Why an exhibition in the underground levels of the Colosseum, already a ‘museum within a museum’?

The answer lies in the cultural strategy characterizing the actions of the Parco archeologico del Colosseo: the aim is to widen the cultural offer, also with innovative exhibitions, which render the function and the historical events of the monuments immediately perceptible, to involve the public in a more informed visit.

It is not unusual for such opportunities to happen within the framework of public-private partnerships: concerning these collaborations, the Parco archeologico has constantly developed a policy of participation with pivotal projects aimed, above all, at broadening both physical and cultural fruition and accessibility.

The exhibition-event ‘Gladiators in the Arena. Between Colosseum and Ludus Magnus‘ falls within this programmatic framework: the occasion is the restoration of the underground corridor, which once connected the Colosseum to the Ludus Magnus. That ancient connection, which had been interrupted since the 19th century by constructing a hydraulic sewer, is now revived thanks to modern technologies.

From the Ludus Magnus, the gladiators came to perform in the Colosseum Arena, acclaimed by more than fifty thousand spectators. Today, those same gladiators, thanks to a sophisticated multimedia experience with holographic projection, perfectly positioned along the Colosseum-Ludus Magnus axis, come back walking on the original opus spicatum floor of the cryptoporticus and advance towards the Arena dressed in their original, colorful armor.

To complete the event and offer the public an additional element of knowledge and understanding, philological reproductions of the armor created by master craftsman Silvano Mattesini are on display along the tour route, alongside original artifacts from the collections of the Parco archeologico del Colosseo, the National Archaeological Museum in Naples and the National Archaeological Museum in Aquileia. Thus, the weapons distinguishing the main couples of gladiators competing for the palm of victory are displayed: the murmillo against the thraex, the retiarius against the secutor, and the murmillo against the hoplomachus.

The exhibition event and multimedia installation are possible thanks to the partnership between the Parco archeologico del Colosseo and the Hornblower Group, a leading US company active in transport and tourism. This partnership was built and imagined starting from the mission of the PArCo, as the scientific and cultural project developed is entirely in line with the education to the memory of Parco’s public, which by its very nature is highly diversified and comes from all the countries of the world. This exhibition design makes it possible to reach everyone without distinction and hand down our history’s roots to present and future generations.

The Director of Parco archeologico del Colosseo – Alfonsina Russo

-

Colosseum and Ludus Magnus: a revived connection

The idea of a temporary exhibition dedicated to the type of gladiators and their weaponry – designed and curated by the Parco archeologico del Colosseo (from July 2023 to January 2024) – originated from the enhancement of the oriental cryptoporticus of the Colosseum, which, as known, connected the stage (arena) to the district of gyms and barracks (Ludi). First established by Emperor Domitian, the best-known and preserved barrack is the Ludus Magnus, the biggest and the only one with part of the structures still in place. It was the place where gladiators were trained and prepared for their performances.

The oriental cryptoporticus is no longer walkable to all its extent: a long sewer pipeline designed to reach the highly populated Esquilino neighborhood disrupted it during the 19th century. Thanks to the PArCo’s missions of restoration and maintenance, the area underneath the Colosseum is now accessible to visitors.

The Ludus Magnus – as portrayed on the marble cadastral map called Forma Urbis – was one of the four gladiators’ training facilities established by Domitian, together with the Ludus Gallicus, the Matutinus, and the Dacicus, as well as the Castra Misenatium, the sailor’s barracks of the Miseno fleet, in charge of maneuvering the velum, the Armamentaria, or the weapons depot, the Saniarium or the hospital, the Spoliarium, where they undressed the fighters’ dead bodies and the Summum Choragium, the scenography factory, and storehouse.

During the Trajan period, perhaps due to static problems in the seating banks (cavea) or the fire of 107 AD, the building underwent a massive restoration, which led to a 1,50-metre elevation of the floor on the quadriporticus around the arena (which remained at the same height as the Flavian period).

During the late-antique period, the building underwent restoration for an extended time – even though there are no specific records – while abandonment started in the early 6th century when it was utilized as an area for modest burials.

In 1937, the excavations for constructing a new building between via di San Giovanni in Laterano and via Labicana unearthed the remains of just the northern half. They were restored between 1957 and 1961 for the opening of the new Municipal Treasury.

The building certainly had two floors and a plan similar to the other barracks. The fragment of the marble Forma Urbis gives us important structural indications. It confirms a rectangular plan with a quadriporticus of Doric style columns made of travertine, accommodation rooms, and services around the central area. It was 2,000 square meters wide and had a cavea accommodating up to 3,000 audience members. The internal pathways were via a corridor behind the service rooms and by stairs to the higher floors (recognizable on the marble plant of the Forma Urbis with a triangular symbol).

The training arena, the curvature of which is still in place, occupied the central courtyard and was built as a scaled-down copy of the Colosseum one (with a ratio of 1:2,5).

The remains of 14 housing cells, about 20 square meters each, were found. It is estimated that the Ludus Magnus could have “hosted” a thousand gladiators.

During the 19th century, the construction of the sewer pipeline to the Esquilino, as mentioned, entirely disrupted the connection between the Colosseum and the gym.

With its original flooring of opus spicatum, today, the cryptoporticus returns to life again and resumes its ancient function. With a unique interactive permanent project and thanks to digital technology and virtual reality, an engaging video-mapping with a holographic projection will allow you to “pass through the wall” that interrupts the connection, bringing back the view of the contemporary archaeological area. Compressed between the streets and the modern palaces that now occupy it, an exciting tale of the Ludus Magnus will bring us inside the historical landscape of the imperial period of the most extraordinary splendor.

The narration of the redevelopment of the Gladiators Cryptoporticus will make this experience of knowledge even more complete, thanks to a temporary exhibit: it will show a selection of the iconic types of gladiatorial pairings that used to perform in fights on the arena floor, entering the Colosseum from the Ludus Magnus and other nearby barracks.

- The Cryptoporticus between Colosseum and Ludus Magnus. Axonometry (by RTI CFR-JANUS-ETS-Geogrà; Parco archeologico del Colosseo)

- The Cryptoporticus between Colosseum and Ludus Magnus. Site plan (by RTI CFR-JANUS-ETS-Geogrà; Parco archeologico del Colosseo)

-

The Origins of Gladiators

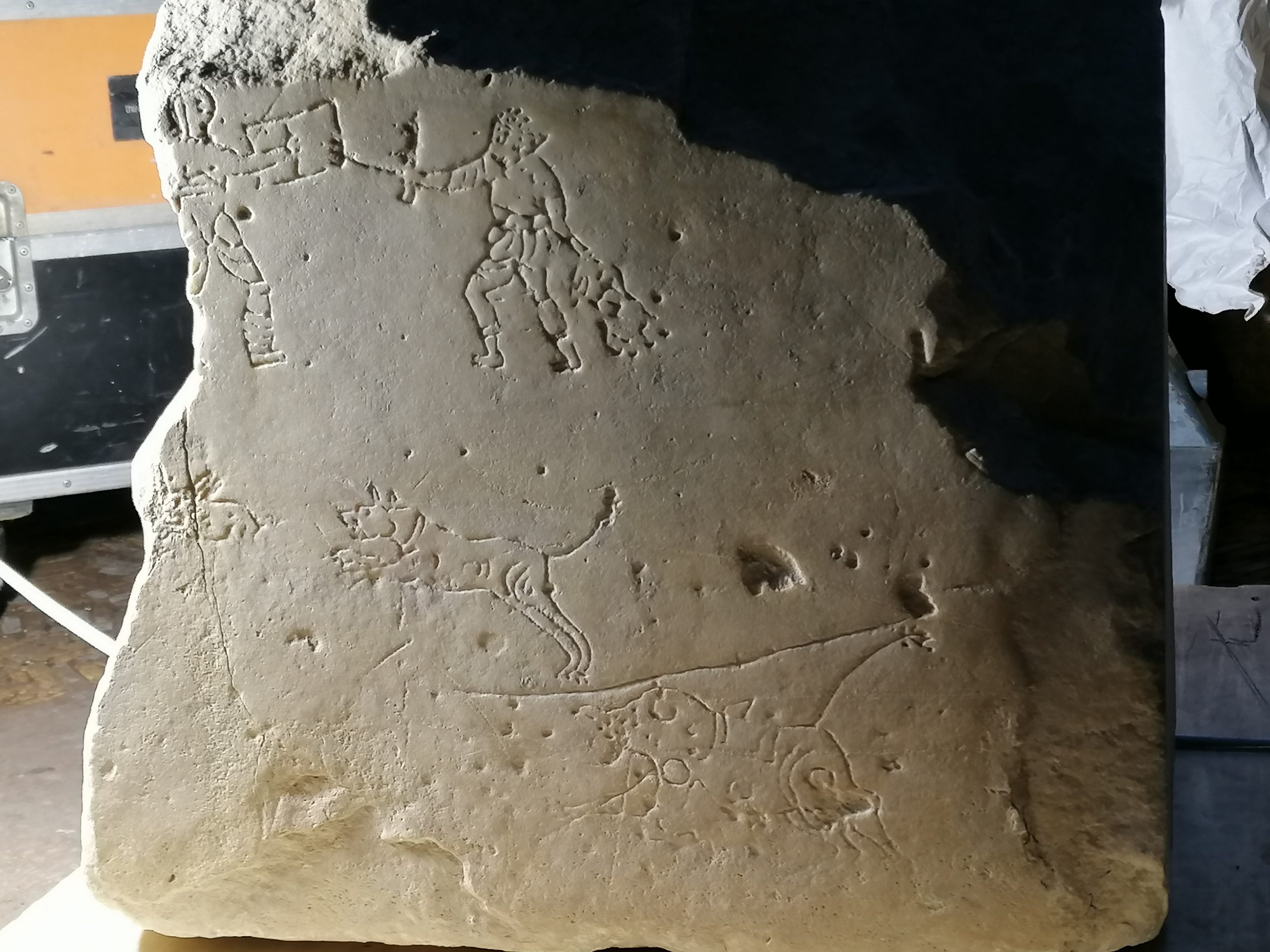

Gladiatorship, which ancient literary sources report of Etruscan origins, appears in the Osco-Samnite fight scenes depicted in some Paestan tombs from the first half of the 4th century BC: they show chariot races, boxing matches, and duels between armed men. In Campania, where the first masonry amphitheaters were built, banquets included fights between men armed as Samnite warriors during performances offered to guests (Livy, 9, 40,17).

The fights between gladiators, munera – meaning tributes or obligations in Latin – made their first appearance in the private sphere as ceremonies connected to mourning the deceased, according to an ancient Mediterranean custom: an example is in the Greek epic poem Illiad, where Homer described the games (as sacred ceremonies) of Achilles during the funeral of Patroclus; another one is in the more recent Latin poem Aeneid, where Virgil remembers those organized by Aeneas for his father, Anchises. According to the sources, the first gladiatorial event with only three pairs of gladiators was staged in Rome in 264 BC by Bruto Pera’s sons in honor of their deceased father (Livy,16; Valerius Maximus, 2, 4,7).

The munus remained private and funerary, at least until the early years of the Empire when the growing public popularity made them an incredible political campaigning tool. If, until the end of the Republic, many private figures kept offering gladiatorial spectacles to sponsor their candidature for public offices during the principality of Emperor Augustus, these spectacles turned into a tangible sign of munificence by the princeps – the real editor – towards the people, to celebrate a victory or honor the imperial family. Later, it was Augustus himself who forbade the performance of more than 120 pairs of gladiators (Tiberius would bring them down to 100) to prevent too many armed men in the employ of one single magistrate.

From then until the 4th century A.C., gladiatorial spectacles represented the most loved public entertainment across all social classes.

Gladiators’ status may vary, as well as their origins. Many of them were war prisoners, as shown by the oldest types of armor, deriving from those of the peoples that the Romans defeated: Samnites, Thracians, and Gauls. Many others were enslaved people; they could be sold by their owner to the Lanista (entrepreneur) or sentenced to combat in the arena after committing a crime. Gladiators might also be freedmen (liberti) and freemen such as cavalrymen (equites), senators, and of imperial blood, like Emperor Commodus, who performed in the Colosseum arena equipped as a secutor. The room 4 displays the stele of Murmillo Quintus Sossius Albus: the ‘tria nomina’, three names, qualify him as a free man and a Roman citizen could only perform as a gladiator by personal choice or special imperial invitation.

Gladiators lived and were trained in the barracks, constituting a familia. They were recruited at the age of 17-18 years, like the army men, and rarely passed the age of thirty, in line with Roman citizens’ average age at death in the imperial era. A gladiator performed in the arena about twice per year: only a few could boast more than 20 fights. The show’s organizer was the editor: he created the schedule and decided the destiny of the defeated. The editor borrowed gladiators from the lanista, the private entrepreneur. In Rome, the editor was the Emperor. Augusts initiated the gladiatorial shows’ administrative organization (Suetonius, Aug., 45), completed by Domitian, and made the most significant effort to categorise gladiatorial classes and armors.

FUNERARY RELIEF WITH GLADIATORS Marble relief belonging to a tomb from Pescorocchiano, the ancient town of Nersae, depicting a fighting scene between two gladiators. On the right hand side is a referee (summa rudis) of the match holding a stick to divide the fighters (end of the 1st century BC). From the permanent exhibition “The Colosseum tells its history”, Colosseum, 2nd level.

-

The Gladiators' Couples

Gladiators were divided into various classes – we know 16 of them – and were categorized based on their origins, weapons, costumes, and fighting techniques.

These classes did not coexist together: in the early ages of gladiatorial combats, gladiators were impersonating the enemy to defeat, as the Samnes, the Gallus, and the Thraex.

The Samnes is the most ancient type of gladiator (Livy, 9, 40). The Gallus might appear during the Caesarian era, later changing his name at the end of the Republican period to Murmillo (Paulus ex Festo 359.1-5; Cicero, Philippicae, 3, 12). The Thraex, identifiable by the typically curved sword –sica– is often mentioned in Roman inscriptions from the 1st-2nd centuries A.D.

As said, the canon gladiatorial classification dates back to the Augustan era, and it was certainly completed by the time of the Flavian imperial dynasty, although further adaptions occurred. An inscription of a burial society in Rome, dated 177 A.D., during the reign of Commodus, lists names and descriptions of numerous types of gladiators based on their armors and categories: thraex, hoplomachus, essedarius, contraretiarius, murmillo, provocator, retiarius.

Based on the training level, an individual gladiator would be referred to as novicius, which meant just enlisted; tiro, a gladiator that had completed the training and wasready for his first fight; veteranus, when he had had at least one combat. At the end of every duel, the palma, a branch of palm, and the corona, a crown probably made of laurel, were given to the winner. The rudis, a wooden sword that acted as a trophy, was gifted to the gladiator at the end of his career.

In the 1st century A.D., a pardon – missio – was usually given to the exhausted gladiator when he gave a clear sign of surrendering by raising his left hand – the one for defense – high with the index finger up, a gesture described in the sources as “ad digitum pugnare”. Afterward, the sine missione fights would prevail, as the social prestige of the editor had to match his generosity.

The most common pairings of gladiatorial classes documented from the 1st century B.C. to the 4th century A.D. were: murmillo-thraex, murmillo-hoplomachus, retiarus-secutor. This exhibition is dedicated to them.

- Clay oil lamps with gladiators fighting. From permanent exibit “The Colosseum tells its history”, on the 2nd level of the Colosseum (Parco archeologico del Colosseo)

- Clay oil lamp with gladiator asking for mercy. From Aquileia, National Archaeological Museum. Imperial age.

-

Room 2 Helmets of Murmillo and Thraex

- HELMET OF THRAEX Reproduction of an original Augustan age helmet in bronze as depicted on the marble relief of Lusius Storax displayed at the Archaeological Museum La Civitella in Chieti. A replica of the relief is on exhibit on the 2nd level of the Colosseum (Silvano Mattesini Collection).

- HELMET OF MURMILLO Replica of the original Julio-Claudian helmet in bronze from the Gladiators Barrack in Pompeii (Silvano Mattesini Collection )

-

Room 3 - Helmets of Murmillones

- HELMET OF MURMILLO Gladiator helmet showing a broad and robust protection grid. Replica of the original bronze helmet of imperial age from the collections of the Staatliche Museen’s Antikensammlung, Berlin (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

- HELMET OF MURMILLO Gladiator helmet with wide facial protection and medallion with Hercules. Replica of the original bronze one of imperial age from the British Museum, London (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

-

Room 4 - Murmillo and Thraex

SHOWCASE 1

THE MURMILLO GLADIATOR

As the secutor (seeker), the murmillo belongs to the scutarii, the category of gladiators using a big rectangular shield for defense. He wore a defensive armor characterized by a helmet with a brim folded on the sides for eye protection, made with a wide grid that gave them overall “good” vision. Their weaponry consisted of a gladius, an iron blade 40-50 cm long, completed with a short greave (ocrea) on the left leg and the sleeve (manica) on the right arm, stuffed with different linen or hard leather layers. The ocrea was secured to the calf by laces anchored to bronze eyelets.

Despite the heavy and impenetrable armor, his classical opponent, the thraex, jumping over the shield and using his fearsome curved sword (sica), could tear the murmillo’s back at the hip or shoulder blade level.

THE THRAEX GLADIATOR

The thraex – named after his land of origin (Thrace) – is the highest representative of the parmularii category, the gladiators with small rectangular shields (parma). He is the usual opponent of murmillo.

The thraex, wearing a helmet with a griffin-shaped crest (lophos), is easily recognizable by his peculiar weapon called “sica supina“, a sword originating in Eastern Europe in the shape of the beak of a flying griffin. The hook-shaped edge hit the back of the opponent, which was usually the murmillo.

The shield was smaller than the scutarii’s ones: because of the shield’s small dimensions, the thraex had his thighs clad in high greaves (ocreae) up to the groin.

The protection on exhibit – a reconstruction of the original bronze one found in the Barrack of Gladiators in Pompeii, now at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples – represented a valuable parade accessory. It is a very heavy bronze cast with highly elaborate decorations: the upper part depicts laurel and oak leaves and ears of wheat. In between the ocreae and the gladiator’s skin was a padded layer of protection.

- Funerary stele of the Murmillo gladiator Quintus Sossius Albus. From Aquileia, National Archaeological Museum. 2nd century AD.

- Complete armor of Thraex gladiator on the right and Murmillo gladiator on the left (Private collection Silvano Mattesini)

SHOWCASE 2

- Miniature amber gladiator helmet of Murmillo. From Aquileia, National Archaeological Museum. Imperial age

- Bone game token with Murmillo gladiator. From Aquileia, National Archaeological Museum. Imperial age

- Miniature amber gladiator helmet of Scutarius. From Aquileia, National Archaeological Museum. Imperial age

- Bronze helmet of Murmillo gladiator. On the calotte are scenes with the personification of Goddess Roma Victorious wearing a combat helmet in an Amazon outfit and bare breasts. From Pompeii, Gladiators Barrack. Second half of the 1st century A.D. Naples, National Archaeological Museum

SHOWCASE 3

- Clay statuette of Thraex gladiator. From Aquileia, National Archaeological Museum. Imperial age

- Bronze helmet of Thraex (Hoplomachus) gladiator. On the forehead is depicted a palm tree and on the top there is the head of a griffin. From Pompeii, Gladiators Barrack. First half of the 1st century A.D. Naples, National Archaeological Museum

-

Room 5 - Secutor, Retiarius e Provocator

SHOWCASE 1

Seat from the Colosseum bleachers (cavea) bearing graffiti depicting a fight between a Secutor and a Retiarius. From the permanent exhibition “The Colosseum tells its history”, Colosseum, 2nd level. 2nd-3rd century A.D.

SHOWCASE 2

THE RETIARIUS GLADIATOR

The retiarius wore a wide loincloth (subligaculum), a belt (balteus), and a strong protection that was put on the left arm (manica) as it was the area most commonly hit by the secutor. The retiarius also wore the galerus, a metal plate on the left shoulder to protect his throat. He did not have a shield or a helmet, his only defensive weapon, besides the net (rete) and the trident (Festus, p. 358), was the dagger (pugio).

The retiarius is a new category of gladiator created at the beginning of the imperial age. The lack of the “typical” armor gives it more agility, mobility, and dexterity to compete against his opponent, the secutor, and his military-level power. The trident was his fearsome and effective weapon, with a decisive breakthrough as both hands held it. A well-struck blow must have resulted in significant trauma to his opponent, no matter the precision of the shot or the type of protection the secutor had.

The seeker or secutor (Isidore of Seville, Origines, 18, 55) is also known as the contraretiarius, as the retiarius was his only opponent.

His helmet was egg-shaped and smooth and was designed to avoid any grip on the grasp of the trident and the net of his enemy, the representative of the god Neptune. The weaponry of the secutor consisted of a short, straight, and not bulky sword, the gladius, a short greave (ocrea) on the left leg, and a padded sleeve (manica) to protect the hand. He was equipped with a large shield (scutum), of various types, sometimes with a semicircular top to protect him from the blow of his enemy’s trident. He defended his throat by wearing a metal or hardened leather polygonal guard, often with spikes.

A second homonymous contraretiarius, identified as cutter, or scissor, had the same secutor helmet but did not have a shield to protect himself from the trident’s power. Therefore, he utilized the typical double headed hammer and a sharp dagger. His defensive armor was scale cuirass (lorica squamata) that started below the groin, one of the sturdiest pieces of military uniform.

Complete armor of Retiarius gladiator on the right and Secutor gladiator on the left (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

Next to the showcase 2:

WEISENAU HELMET

Military helmet of the Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix. Similar to the so-called Weisenau type, it was utilized by a provocator during the imperial age: it has a large neck guard and a solid front buffer. Replica of the original bronze helmet of Trajan age, now preserved in Bonn at the Rheinisches Landesmuseum.

MILITARY HELMET OF PROVOCATOR

Replica of a military helmet, utilised in war with the cheekguards in boiled leather: the typology is dated to the 2nd century B.C., with a front drop that seems to work well as a buffer.

- Military helmet of the Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix. Similar to the so-called Weisenau type, it was used by a Provocator during the imperial age: it has a large neck guard and a solid front buffer. Replica of the original bronze helmet of Trajan age, now in Bonn at the Rheinisches Landesmuseum (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

- Helmet of Provocator gladiator. The type is dated to the 2nd century BC (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

SHOWCASE 3

PROVOCATOR FROM THE IMPERIAL AGE

This gladiator type has a long story and a substantial evolution. It perfectly represented the fencing of equal and opposite forces, so much so that it is considered the “experimental” corp of the Roman legions. The equipment was typical of the scutarii with comprehensive defense and military-type gladius, utilized mainly at the blade tip. He wore a short greave (ocrea) on the left leg and chest protection (cardiophilax). The helmet was usually of the Gallic type, closed and without the crest, with frontal buffer and neck protection. The shield is rectangular.

- Complete armor of Provocator gladiator (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

- Complete armor of Provocator gladiator (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

-

Room 7 - The Hoplomachus

The hoplomachus is part of the parmularii category and uses a round shield (parma) with a short, sharp dagger or machaera. In addition to the high greaves (ocreae) that reach the groin, he has extensive padded protections for the legs. The chest has no protection, as the attack was granted by his most offensive weapon, the spear.

He wore a griffin-shaped helmet with a high brim adorned by plumes. The shield on exhibit is the replica of the original one from the Gladiators Barrack of Pompeii and originally on display at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples: it has a decoration with olive leaves coated in silver and copper. In the center is a Medusa’s head surrounded by the same naturalistic motives.

- Metal alloy statuette of Hoplomachus gladiator. From Aquileia, National Archaeological Museum. Imperial age

- Complete armor of Hoplomachus gladiator (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

- CLAY OIL LAMP WITH FRIEZE OF WEAPONS Colosseum, permanent exhibition “The Colosseum tells its story”, 2nd level 1st century A.D. Parco archeologico del Colosseo

-

Room 8 - Parade Helmets

PARADE HELMET OF MURMILLO

Helmet of murmillo in cast bronze: on the calotte are scenes with the personification of Goddess Roma Victorious as a bare breasted Amazon wearing a combat helmet.

She leans on a shaft with her left hand, holding the scepter with her right hand. She tramples on the enemies’ weapons, which are symbolically represented at her feet in a submissive pose. On the sides are other prisoners with their hands tied behind their backs. The decoration ends with two flying Victories looking at their enemy’s trophies, which are formed by shields, armor, and helmets typical of Northern Europe, with real or fake hair. The cheek-pieces are also plain and unadorned.

Helmet of Murmillo gladiator in cast bronze: the helmet depicts the personification of Goddess Roma Victorious as a bare breasted Amazon wearing a combat helmet. The replica on exhibit is made from the original mold of the second half of the 1st century A.D. from the Gladiators Barrack in Pompeii, currently at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (Silvano Mattesini Collection). The original is desplayed in room 4.

PARADE HELMET OF THRAEX (HOPLOMACHUS)

The bronze cast helmet on exhibit is characterized by a hemispherical calotte with a wide buffer brim that, unlike the other gladiators’ helmets, is more linear and has a slight folding close to the parietal bone. The complete face protection leaves only two holes for the eyes, covered by a grid: a particular design indicating the production during the Julio-Claudian age. A palm tree on the forehead represents the “palma lemniscata“, usually given to the fight winner. On the bronze visor are two little round shields (parmae) and two crossed spears, while on the top is the head of a griffin. Those symbols likely belong to an hoplomachus or a thraex gladiator (both parmularii, as they were armed with parmulae, which are smaller shields). On the sides of the helmet (galeae), there are two small openings for inserting plumes. Under the buffer brim are bronze reinforcements to protect against blows from the sides.

Helmet of Thraex (Hoplomachus) gladiator in cast bronze. On the forehead is depicted a palm tree and on the top there is the head of a griffin. The replica on exhibit is made from the original mold of the first century of the 1st century A.D. from the Gladiators Barrack in Pompeii, currently at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (Silvano Mattesini Collection). The original is displayed in room 4.

PARADE HELMET OF MURMILLO

The falling of the city of Troy (Ilion), or Ilioupersis, is the main subject on this typical parade helmet of murmillo, made of cast bronze. The ancient Greek epic poem, of which only a few fragments remain, is attributed to Arctinus of Miletus, as it was probably written in the 7th-6th century B.C. It focuses on the final phase of the Trojan War and the enterprises of Aeneas, with the groups of Neoptolemus and Priam and Ajax and Cassandra. The focus of the narration is on Athena and the birth of Rome. The lower section of the mask is widely decorated as well. The illustration of the city walls patterns the entirety of the background of the crest. Crests are richly decorated in great detail, and well contained, usually without feathers (unlike the showy helmet of his typical opponent, the thraex).

Helmet of Murmillo gladiator with scenes of the the falling of Ilio (Troy). The replica on exhibit is made from the original mold of the second half of the 1st century A.D. from the Gladiators Barrack in Pompeii, currently at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (Silvano Mattesini Collection)

-

The Gladiators' Glossary

GLOSSARY

Balteus: high belt | waist-band

Cavea: seats

Cardiophilax: chest protection

Corona: crew

Editor: shows organiser

Familia: group of gladiators belonging to a lanista

Equites: cavalry man

Galea: helmet

Galerus: metal protection of the retiarius’ left arm

Gladius: iron sword

Lanista: private entrepreneur

Libertus: free man

Lophos: crest

Machaera: sword

Manica: arm protection from shoulder to hand

Munus/munera: tribute, obligation, gift

Novicius: newly enlisted gladiator

Ocrea: leg protection

Opus spicatum: small brick floor arranged in a fishbone pattern

Palma: palm

Parma / parmula: small shield

Pugio: pugnale dagger

Rudis: wooden sword

Scutum: large rectangular shield

Subligaculum: wide thong

Summa rudis: referee

Sica: curved dagger

Summa rudis: referee

Tiro: a gladiator that has completed the training and is now ready for his first fight

Veteranus: gladiator who has fought at least one fight

-

Bibliography

Bibliography about Ludus Magnus

A.M. Colini, L. Cozza, Ludus Magnus, Roma 1962.

S. Serra, A. Ten, Ludus Magnus: dati per una nuova lettura, in Scienze dell’Antichità, 19.1., Roma 2013, pp. 203-218.

Bibliography about gladiators

A. Augenti, Spettacoli del Colosseo nelle cronache degli antichi, Roma 2001.

A. La Regina (a cura di), Sangue e arena, catalogo della mostra (Roma, 22 giugno 2001 – 7 gennaio 2001), Electa, Milano 2002.

M. Papini, Munera gladiatoria e venationes nel mondo delle immagini, Accademia nazionale dei Lincei, Roma 2004.

F. Guidi, Morte nell’arena. Storia e leggenda dei gladiatori, Mondadori, Milano 2009.

C. Mann, Gladiatori, Il Mulino, Bologna 2014.

S. Rinaldi Tufi, Gladiatori. Una giornata di spettacoli, Quasar, Roma 2018.

P. Arena, Gladiatori, carri e navi. Gli spettacoli nell’antica Roma, Carocci Editore, Roma 2020.

V. Sampaolo (a cura di), Gladiatori, catalogo della mostra (Napoli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, 8 marzo 2021 – 30 giugno 2021), Electa, Milano 2020.

-

Colophon

GLADIATORI NELL’ARENA

Tra Colosseo e Ludus Magnus

Colosseo, 20 luglio 2023 – 7 gennaio 2024

Ministero della Cultura

Ministro

Gennaro Sangiuliano

Capo di Gabinetto

Francesco Gilioli

Segretario Generale

Mario Turetta

Direttore Generale Musei

Massimo Osanna

Capo Ufficio Stampa e Comunicazione

Andrea Petrella

La mostra/ The exhibition

a cura di/ edited by

Parco archeologico del Colosseo

Alfonsina Russo

Federica Rinaldi

Barbara Nazzaro

Silvano Mattesini

Direttore

Alfonsina Russo

Segreteria del Direttore

Gloria Nolfo

Luigi Daniele

Fernanda Spagnoli

Funzionario archeologo Responsabile del Colosseo

Federica Rinaldi

Funzionario architetto Responsabile tecnico del Colosseo

Barbara Nazzaro

Staff del Colosseo

Elisa Cella, Funzionario archeologo

Angelica Pujia, Funzionario restauratore

Valentina Mastrodonato, assistente tecnico

Emilia Valletta (architetto, Ales)

Responsabile Servizio Valorizzazione

Daniele Fortuna

Ufficio Fundraising

Ines Arletti

Andrea Caracciolo

Responsabile Ufficio Bilancio e contabilità

Paola Cuzzocrea

Responsabile Ufficio gare e contratti

Massimo Epifani

Servizio Comunicazione

Federica Rinaldi

Astrid D’Eredità

Idea espositiva

Federica Rinaldi

Ricostruzioni armature

Silvano Mattesini

Interventi di restauro e manutenzione criptoportico est

Barbara Nazzaro

Angelica Pujia

RWS

Tempus et Opera

Supervisione interventi di consolidamento strutturale

Stefano Podestà

Impianti elettrici

A.F. Impianti

Impianti anti intrusione

Ciancarella Duilio

Coordinatore della sicurezza

Patrizia Formichella

Documentazione grafica criptoportico est

RTI CFR Janus Geogrà ETS

Installazione multimediale

Progetto Katatexilux

Realizzazione allestimento

Handle Art & Design Exhibition

Trasporti e movimentazioni delle opere d’arte

TRAART – Trasportiamo S.r.l.

Testi didattici

Federica Rinaldi

Silvano Mattesini

Traduzione dei testi

Elisa Cella

Francesca Pandolfi

Identità visiva della mostra

Daniela Petrucci (Ales)

Enti e Musei Prestatori

Parco archeologico del Colosseo; Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli; Direzione regionale musei del Friuli Venezia Giulia – Museo archeologico nazionale di Aquileia (UD); Collezione privata Silvano Mattesini

Si ringrazia / Thanks to

Per la concessione d’uso dell’immagine “Pianta marmorea severiana: Ludus Magnus” (frammento 6b-f = inv. AntCom 00951 – Roma, Musei Capitolini, Parco Archeologico del Celio – Archivio Fotografico dei Musei Capitolini) si ringrazia © Roma – Sovraintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali

Per la Sovrintendenza Capitolina si ringrazia la dott.ssa Simonetta Serra, archeologa responsabile dell’area del Ludus Magnus

Si ringrazia tutto il personale di vigilanza e accoglienza del Colosseo

L’esposizione e l’installazione multimediale sono stati possibili grazie alla partnership tra il Parco archeologico del Colosseo e la Hornblower Group, primaria azienda statunitense attiva nei trasporti e nel turismo, fondata nel 1926 a Boston.

The exhibition and multimedia installation was made possible thanks to the partnership between Parco archeologico del Colosseo and the Hornblower Group, a leading transportation US group, founded in 1926 in Boston.

-

Download the ebook